Art + Auction

Believe It or Not

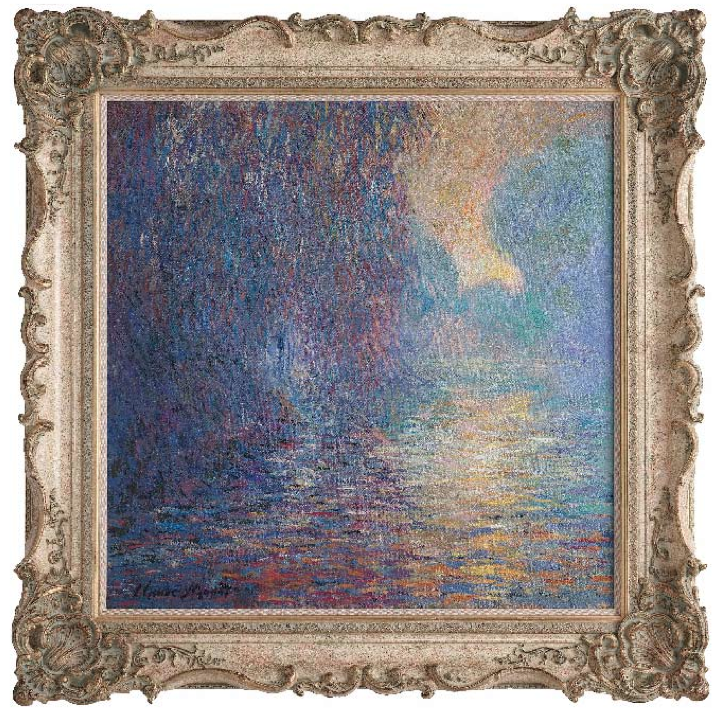

The meeting room at London’s Bar Council is an unremarkable space, strewn with rectangular tables set with stacks of coffee cups. But last spring, an extraordinary art show hung on its walls. there were three Monet landscapes, a rare Giacometti portrait of a long- faced man, a Juan Gris still life, even a Cubist nude by Picasso. each was signed by its putative author. And each was painted so convincingly that it was hard to believe one person had created them all.

That man is John Myatt, a star among copy artists. In 1999 he spent four months in prison for making paintings just like these. His story, currently being turned into a Hollywood movie, started in the mid-1980s. Myatt placed a classified ad in a satirical london paper offering 19th- and 20th-century “genuine fakes” for £150 (about $250) and up. Criminal genius John Drewe contacted the artist and convinced him to forge “new” works by nine modern masters. Drewe fabricated the provenances, going so far as to alter the archives at the victoria & Albert Museum to make the fabrications more convincing.

Looking back, Myatt says that his forgeries were “unbelievably shoddy.” Yet before being arrested, a decade later, Drewe managed to sell nearly 200 of the artist’s fakes to serious dealers and at auction houses in London and New York, including Sotheby’s and Christie’s, for tens and even hundreds of thousands of dollars apiece. Scotland Yard has called the scheme the“biggest art fraud of the 20th century.” When Myatt completed his jail sentence, he received a phone call from the detective who had apprehended him and who now wanted to commission a portrait. Several barristers who had worked on the case also asked about buying pictures, and the artist soon discovered he could earn a respectable living selling ersatz masterpieces, as long as his customers knew what they were buying.

Myatt and his avid clients are just one part of an active international market for fakes. From Paris to Dubai to New York, demand for these works is strong, even among a surprising number of well-heeled buyers. “People are fascinated by the subject. They are fascinated with the idea of getting away with something, fooling the experts,” says Nancy Hall-Duncan, senior curator at the Bruce Museum, in Greenwich, Connecticut, and organizer of the museum’s “Fakes and Forgeries: the Art of Deception” exhibition, on view through September 9. The show, which Hall-Duncan emphasizes is “educational,” includes everything from a knockoff of a Cycladic marble head to Han van Meegeren’s infamous 20th-century forgeries of Vermeer paintings, as well as several works by Myatt. “This is a big-money field,” says Hall-Duncan. “And it’s important that forgeries be exposed.”

Meanwhile, in Paris’s seventh arrondissement, Laurent Monnier, a soft-spoken Frenchman, runs a gallery called l’Oeuvre Copiée out of his apartment. For the past 20 years, Monnier has sold reproductions of famous paintings to interior decorators, high-end hotels and owners of multiple châteaus looking for art that goes with their antique furniture yet won’t cause much grief if stolen. He specializes in Old Masters and has 20 artists working for him, mostly French and Polish. Behind his couch hangs a deftly rendered copy of one of Francesco Guardi’s Venetian views priced at about $2,700, framed. “I have some very rich customers, but they are mostly interested in the decorative aspect,” says Monnier, citing an American couple who recently bought an apartment on the Quai d’Orsay and whose decorator came looking for reproductions of 18th- century French paintings.

Another dealer of high-quality copies is Christophe D. Petyt, a dashing Frenchman with a taste for Versace and a business so successful he regularly hobnobs with his jet-set customers. He estimates that he has sold close to 5,000 reproductions over the years, at prices more typically reserved for “real” artworks.

Petyt got his start in 1991, when he came upon a photo of Van Gogh’s 1890 portrait Mademoiselle Ravoux. He wanted the painting, but as a 21-year-old business student, he had no chance of buying it. Instead he asked an art student acquaintance to make a copy. It occurred to Petyt that there might be a market for such works, and he ordered 20 more reproductions of masterpieces from his friend. The following year he and two associates convinced the royal Mansour hotel in Casablanca to host an exhibition. All the paintings sold, with 60 more on order.

Petyt still does most of his business in affluent markets such as Dubai, Monaco and Palm Beach, by setting up temporary exhibits in the private salons of luxury hotels. He employs a stable of 83 professional artists with individual styles who, he says, “get a kick out of making copies on the side.” Petyt pays them per painting, with the amount depending on the complexity of the commission. His customers, like Myatt’s, tend to prefer the Impressionists and avoid the better-known works (the Mona Lisa in his inventory is still unsold). His typical buyer is, in his words, “Monsieur tout-le-Monde,” an average Joe who dreams of owning a masterpiece but whose budget falls a few million dollars short. Petyt’s prices range from $7,000 to $40,000. His biggest sale was of a double-sized copy of Renoir’s famous Déjeuner des Canotiers, 1880–81, for which the Saudi Arabian prince who commissioned it paid nearly $100,000.

Wealthier clients refused to be identified or interviewed for this article. “There’s a whiff of paranoia about the whole thing,” says Myatt. But Petyt explains that well-to-do collectors have several reasons for buying copies. For some, it’s the inaccessibility of the real painting. Such was the case for a German man in Marbella, Spain, who coveted Paul Gauguin’s 1892 Nafea Faa Ipoipo (“When Will You Marry?”). He might have had the means to buy the original, but it belongs to the Rudolf Staecheline Family Foundation, which wasn’t interested in selling the work, now on view at the Kunstmuseum, Basel. So he settled for a reproduction provided by Petyt.

Many clients, the dealer says, come to him because they are selling works from their collections to acquire something else and want to sidestep the awkward questions that can arise. “Even if they’re replacing [their picture] with something more expensive, their friends assume they have money problems when they see the first one gone.” A copy of the discarded painting avoids what Petyt calls this “small inconvenience.” The originals in such cases are never very high profile, but they can be pricey (he mentions a Monet that went for $25 million in Switzerland) and are sold on the private market.

Other customers actually do have financial worries that require them to reluctantly sell heirlooms, says Manuel Schmit. His Paris gallery deals primarily in original masterworks, but Schmit will occasionally commission a copy from a local artist for a wistful client who desires a “well-made trace of the family patrimony.”

Some collectors might keep an original work in a safe and exhibit a copy in its stead. Others decide to avoid the genuine articles’ security risks and associated costs completely. One of Petyt’s clients, a Franco–Costarican heir to a considerable fortune who prefers to remain anonymous, explains that he has filled his many residences with copies because “I find it ridiculous to spend $5 million on an original artwork, just to spend the same amount again every 10 years in insurance.” This client recently bought himself a private plane. “He will spend $25 million for that, but not for a painting,” says Petyt.

Today, with an influx of new buyers eager to acquire big-name artists as the supply of blue-chip pieces dwindles and original works are selling for amounts that even some multimillionaires find obscene, the most pragmatic reason for buying a copy is cost. “How can you justify those prices when they’re based on nothing, just canvas and paint?” asks one dealer of high-end fakes. “They’re not even noble materials. Van Gogh was dead broke; he used the cheapest paints.” The dealer himself once sprung for an authentic Picasso but sold it soon afterward because “it seemed idiotic.” For many like him, authenticity takes a back seat to practicality.

“Obviously, if something costs £20 million and you don’t have the money, a copy is a way for you to get the same image on your wall for substantially less,” says James Roundell, of the Simon Dickinson gallery, in London. Still, although fakes are selling briskly, experts like Roundell and others insist there is no correlation between the increasing price or rarity of quality originals and the demand for reproductions. As Schmit notes dryly, “My clients with money, of course they’d all like to own Van Gogh’s Irises or Monet’s Soleil levant. But that’s not a reason for them to go and order a copy.”

“Rich people are often more intelligent than we give them credit for,” says Myatt, whose customers include an American collector who owns two real Van Goghs and one by him. “I think they like having fake paintings around. It amuses them to think they could have spent millions.” Myatt even claims that buying a fake has a certain reverse snob appeal, freeing you up to pick something because it goes with the curtains and to “get beyond all the stupid experts, silly pompous nonsense that goes with connoisseurship.You can shrug all that stuff off, tell all the experts to stick it where the sun doesn’t shine.”

These days Myatt’s works sell for around $6,000 each, but one of his Monets recently went for nearly $30,000 at Washington Green Fine Arts, a gallery in Birmingham, U.K., that now represents the artist. Marketing director Samantha Jackson says that Myatt’s paintings “have more color” than the Impressionist’s. In a show last February where a real Monet was shown alongside six of the artist’s fakes, she insists that “everybody preferred the Myatts. They were not quite as drab.”

While some will dismiss such claims as absurd, the market for copies does have a distinct pecking order. Highbrow dealers, like Petyt and Monnier, turn up their noses at the flood of shoddy reproductions at the low end of the market, most of them from Dafen, a village in southern China. There, an estimated 8,000 to 10,000 painters churn out millions of cheap oils every year, most of them copies of Western masterpieces. the paintings are shipped overseas, where they become fodder for Internet-based galleries and Wal-Mart, which unloads them for a few hundred dollars each, framed.

One of these paintings has about as much possibility of confusing the experts as a poster. The same cannot be said about the reproductions that Petyt sells, which are startlingly accurate, down to the dimensions and paint thickness. The canvases are aged with black tea and dust and gilded frames are bored with tiny holes like woodworm marks. Shocked by the verisimilitude, the Toulouse-Lautrec museum in Albi, France, and Renoir’s descendants launched a lawsuit against Petyt and some other copy dealers in the early 1990s. The suit was unsuccessful, since copyright protection expires 70 years after an artist’s death.

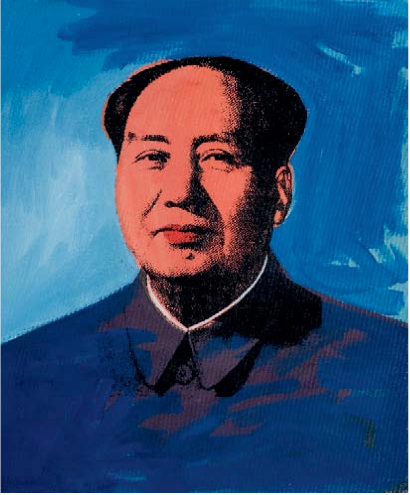

But when asked recently about the legitimacy of Myatt’s current crop of signed fakes, the Picasso Administration in Paris (the organization that administers and monitors the rights to the artist’s work, name and likeness) responded that no authorization had been granted and that Myatt’s Picasso imitations were therefore “illicit.”

Legal copies bear an inscription on the back or some sign to clearly denote that they are not genuine. The collector’s intention is another matter. Some, especially those with money, don’t hesitate to claim bragging rights. Petyt mentions a client who has a Palm Beach home filled with art that would be worth tens of millions if it were real. “He only buys copies of works from private collections, never museums. then he shows his friends the catalogues and says, ‘See? that’s mine.’ ” Myatt’s American client with the real and erstaz Van Goghs often quiz-zes his visitors on which of the paintings is the phony.

Roundell, who was head of the Impressionist and modern art depart- ment at Christie’s london during Myatt’s criminal years, recalls reject- ing several of his fakes because of concerns about their authenticity. When asked about the counterfeiter’s talent, Roundell says that in general, “people copying with a view to profiting have great skill but no real original spark.” Schmit adds that “a trained eye will always see the difference.”

It’s easy to understand how confusion might arise about these works later, though. London dealer and former Sotheby’s director Peter Nahum unwittingly bought a couple of Myatt’s forgeries from Drewe’s runners in the 1980s and ’90s. He calls fakes an “irritation,” saying, “as history allows them into the market, they get blessed. The problem is that 300 years down the line, since the copy was made only 50 years after the original, you have trouble telling whether it’s original or not.”

Computer chips can be removed, backs of paintings relined. Forensics can help to date the paint. But high-tech analysis is expensive and, as Myatt points out, “might only mean that at some point a painting’s been through a dealer’s hands and he’s retouched it.”

Myatt feels no guilt about any of his fakes, legal or illegal. “Other people might think it’s blasphemous. I think it’s funny,” he says. “I’m secretly pleased that my little babies are out there developing new histories, finding new owners.” He recalls a time when his profession was considered a noble art, an homage to a master. Scotland Yard says 120 of Myatt’s illicit forgeries are still unrecovered, hiding in museums or personal collections, and the artist admits that “if anybody showed me one and asked, ‘Did you paint it?’ I would deny it. My fakes are out there, period.” And he’s painting more all the time.