Wallpaper

Finding Light in Charcoal

In 1990, Lee Bae was a classic starving artist, a 34-year-old immigrant from South Korea working in a squat in a dodgy suburb of Paris. Lacking money for paint, he went to a service station and bought a bag of charcoal. Sitting in his current Paris studio, a two-storey apartment overlooking the Canal de l’Ourcq, he recalls, ‘The first time I saw it, I thought: “Ah, I come from a place that knows all about black.” He explains that Koreans had been making ink sticks from the soot of pine trees since around 4000BC. Now, far from home, ‘It was charcoal that gave me my culture.’

In Korea, charcoal is considered a purifier, a protector, a part of daily life. Every year, for the Moon House Burning festival, Lee’s home town lights a bonfire of pine trunks covered with wishes on paper, then distributes the charcoal to villagers. Traditional houses are constructed on a charcoal foundation, to keep humidity and insects away, and Korean families also hang charcoal over the door when a baby is born, to ward off sickness. And in charcoal, Lee found artistic inspiration, ‘the richness of a poor material’. Back home, he had worked mainly in colour. Now he found that charcoal contained an infinite variety of blacks – and that was enough.

At first he employed it like a crayon on paper. Then he started mixing it witha semi-transparent fixative, caking it thickly onto canvas in large geometric shapes with blurry edges. At times, he polished shards of charcoal to highlight the different ways their wood grain reflected the light, arranging and gluing them onto the canvas like a mosaic in black. In 1997, he bought a traditional hanjeungmak sauna, located in the mountains near Cheongdo (where he was born), and started having his charcoal made there. Tree trunks were held together with elastic cord in the kiln, and Lee presented the charred results, still bound, as sculptural installations.

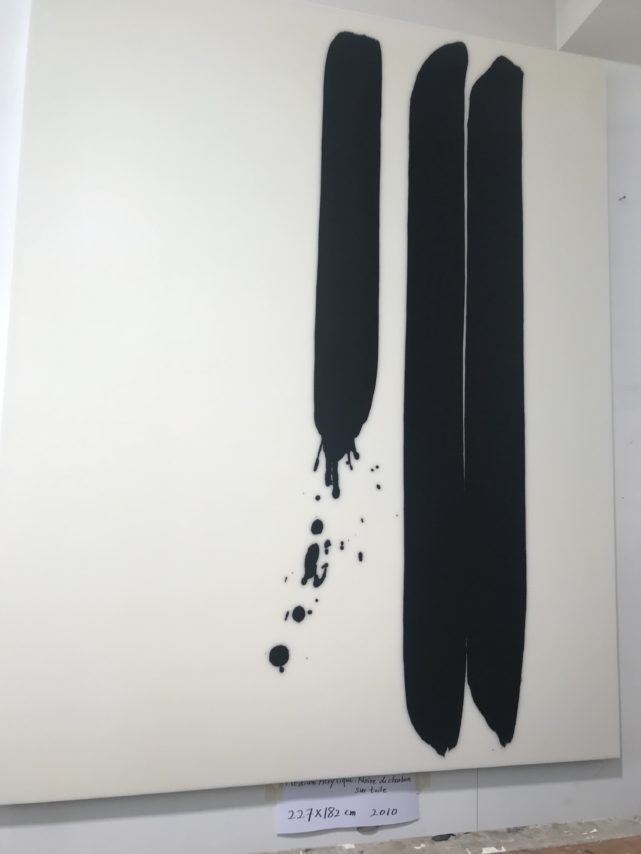

In the early 2000s he decided to modify his painting technique, marking the transition with a symbolic ceremony in which he tossed his charcoal powderup into the air. He continued to use the material, but differently, contrasting it with a synthetic medium in white. Whereas they had been rough in texture, his paintings now became smooth and waxy-looking. He mixed a base from acrylic medium and resin, then painted a motif over it in carbon black. By alternating the two techniques in layers, he obtained a flat surface with surprising depth.

The black motif was embedded densely into the creamy white background, reminiscent of how Korean hanji paper absorbs India ink. ‘I wanted an effect like calligraphy,’ says Lee. But his symbols are not calligraphy; they’re abstract. Every morning, he does 20-30 quick sketches on paper with a brush and either charcoal paint or India ink. These are unplanned and spontaneous, as he allows his subconscious, ‘the memory of his body’, to guide his hand. Later, he chooses the sketches that please him and transfers the motifs onto canvas.H

He demonstrates, mixing charcoal paint from Korean bamboo, pine and water, then making a series of small strokes on paper with his paintbrush. The effect is simple yet stunning – three dimensional figures appear to be leaping off the page. ‘I don’t look for the concept until after the gesture,’ he explains. He points at a large painting with three bold horizontal lines that remind him of a farmer’s field. Another makes him think of the bamboo he played with as a child. A curving line is like a river, while a dramatic swirl recalls an orchestra conductor. Each line is remarkably precise; even drips like Jackson Pollock splatters have been meticulously applied one by one.

The artist was born in the village of Cheongdoin 1956, when South Korea was desperately poor. His father was a peasant and, as the eldest child of five, Lee was expected to take over the farm. But when he was 13, an art teacher at his school took an interest in his work and asked for a sketch, which would later earn him a national student art prize. As a result, he received a grant to study art at a high school in the nearest big city, then pursued fine arts at university in Seoul. He left South Korea hoping to expand his horizons and develop an international career.

His original plan was to live in the US, but he found the art scene there overwhelming. ‘I thought I might lose myself and become American, when the motivation for leaving my home was to find my Korean identity.’ Paris seemed softer and more welcoming, and there was a Korean art community – he served as Lee Ufan’s assistant for seven years in the 1990s. He learned to speak French and converted to Christianity, but has never lost his connection to South Korea, where he returns three to four times a year. He maintains studios in Cheongdo and Seoul, and currently has plans for a third on Ulleungdo Island. For more than 20 years, his charcoal has come from his kiln in the mountains, from a variety of newly fallen trees.

Virginia Moon, assistant curator of Korean art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, who went to meet the artist in South Korea last summer, says, ‘Lee Bae’s works do not insist; they simply are. Therein lies their effortless power and peaceful grace.’

Galerie Perrotin, which has worked with Lee since 2017, is hosting an exhibition of his work in New York this winter. The gallery is showing early charcoal canvases alongside his most recent creations, a forest made from 24 charcoal sculptures and some large-format charcoal drawings. Lee’s techniques have started to evolve again. After his period of smooth paintings, he is returning to the brushstroke. He has also introduced colour, starting with red, peeking out from behind the black. He is even making bronze versions of his carbonised tree trunks. But one thing that does not change is the artist’s fascination with charcoal. ‘There is such strong energy within,’ he says. ‘You set it alight and it burns.’

Read on Wallpaper